By cuterose

Here's why your carrier is so scared of your phone's mobile hotspot

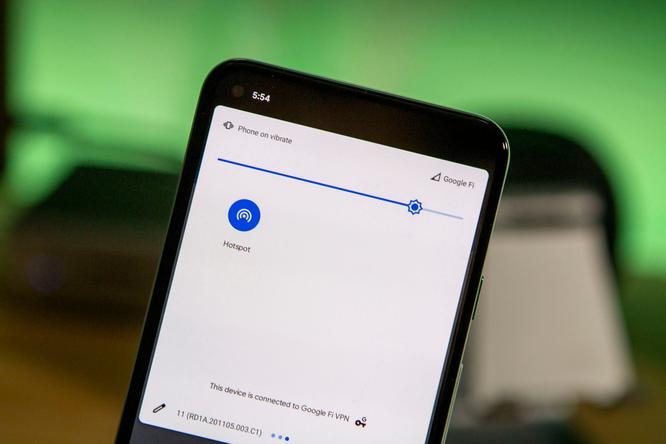

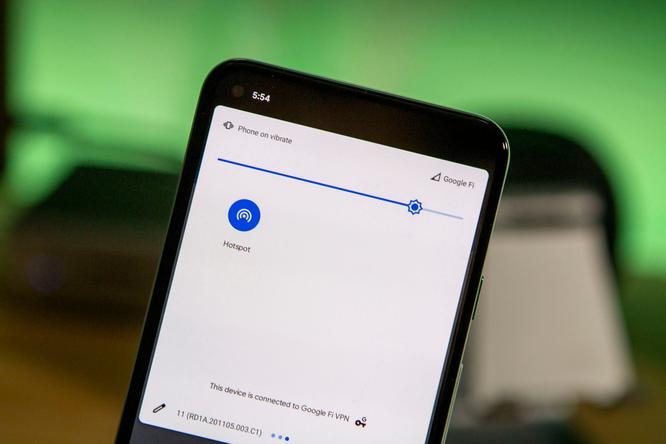

The Palm Pre and Pixi, introduced in 2010, were the first smartphones in the world that could broadcast a Wi-Fi hotspot.

It's clearly a handy feature. Virtually all iOS and Android smartphones today sport the capability (but network operators must also support the service for customers to actually use it).

After all, the utility of creating a portable Wi-Fi hotspot with your phone is obvious to travelers looking to power up their laptops, parents keeping their kids' tablets connected or gamers visiting a friend's house, for example.

In the US, AT&T, Verizon and T-Mobile generally bundle mobile hotspot services in with their expensive unlimited smartphone data plans, using the feature as another reason to encourage customers to upgrade from cheaper tiers of service.

For example, AT&T only offers mobile hotspot services on its most expensive Cricket-branded prepaid unlimited plan. On its standard, AT&T-branded postpaid plans, AT&T does not offer mobile hotspot services on its cheapest "Starter" unlimited plan. But it does offer limited amounts of hotspot data on its more expensive "Unlimited Extra" and "Unlimited Elite" plans.

Data in silos

Now, here's where things get tricky when it comes to mobile hotspot plans. Almost all US network operators limit the service in some way. AT&T, for example, caps its high-speed mobile hotspot data at 40GB per month on its most expensive unlimited smartphone plan, slowing speeds after that threshold. T-Mobile applies a similar 40GB cap to its most expensive unlimited data plan, dubbed "Magenta Max."

These caps are noteworthy considering both AT&T and T-Mobile just removed the caps on their most expensive unlimited plans albeit only for data consumed on the customer's smartphone.

"Your unlimited high-speed data can't slow down based on how much you use," boasted AT&T. "You can't be slowed down based on how much you use," touted T-Mobile.

Except that's not true when it comes to data consumed via customers' mobile hotspots. Both AT&T and T-Mobile still apply a hard limit to the amount of mobile hotspot data available on their premium unlimited data plans.

This means that data consumed by the phone itself checking email or watching Netflix, for example is not limited. But data consumed by the phone's hotspot a tethered laptop, for example is strictly limited. Both scenarios ultimately use the exact same connection the link between the phone's modem and the nearest cell tower but the data consumed in each situation is treated completely differently.

Why?

Device, revenue proliferation

The answer, unsurprisingly, boils down to money. AT&T and T-Mobile view each device in a customers' life as a separate line of revenue. A customer's phone might generate $80 per month in revenues, but a smart watch or a laptop might generate even more.

All of the nation's carriers are already moving toward this approach. For example, they all charge around $10 per month for a customer to add a cellular-capable smart watch to their account, even if that customer is already paying for unlimited smartphone data. The same is true for laptops and automobiles that can connect to 4G and 5G networks.

Now, there's one obvious explanation for this: Operators must service each new connection into their networks. An LTE-capable smart watch might not be able to consume lots of data, but it represents a separate end-point to a mobile network operator. The same is true of a laptop or automobile that sports built-in cellular capabilities.

However, the same is not true for smart watches with Bluetooth. Those types of devices connect first to a customer's phone via Bluetooth and then consume data through that phone's mobile network connection (either Wi-Fi or cellular). And in the case of Bluetooth accessories such as smart watches, operators do not charge extra for the data those gadgets consume.

But the same is not true for a phone's mobile hotspot even though the concept is exactly the same. After all, a laptop that's tethered to a phone via a Wi-Fi hotspot is consuming data in the exact same set-up that a smart watch that's tethered to a phone via Bluetooth is consuming data.

The only difference? One can consume a lot of data, and is therefore viewed as an opportunity for profits by operators.

FWA, not hotspots

The real reason operators are so scared of mobile hotspot capabilities on smartphones first introduced more than a decade ago is because they could instantly cut off a major new source of growth: fixed wireless access (FWA).

Verizon and T-Mobile, and to a lesser extent AT&T, are all hoping that FWA grows into a major opportunity. FWA services like Verizon's 5G Home or T-Mobile's Home Internet are designed to replace customers' in-home Internet connections with wireless options. Meaning, customers would pay around $50 per month, install a gateway inside their home and then run all of their household Internet connections through an FWA service.

Although there are some technological differences between an FWA gateway and a phone's hotspot, the result is the same: both sit inside a home or office, broadcast a Wi-Fi network and then route traffic from that network over a cellular connection. The only real difference is that one device carries a $50-per-month fee and the other does not.

And that's why operators like T-Mobile and AT&T set strict limits on the amount of data customers can consume via their phone's hotspot they don't want those customers to replace their home Internet service with a mobile hotspot.

(There's one important caveat to all this: Verizon has said that the hotspot services on its mobile "Ultra Wideband" millimeter wave 5G network are truly unlimited. However, that network generally does not reach into any homes or offices. It's unclear what Verizon might do as it deploys "Ultra Wideband" services on its C-band spectrum.)

The bigger picture

To be fair, US operators' wireless networks would undoubtedly grind to a halt if their customers suddenly routed all their home Internet activities through their phone's hotspot. Wireless networks run on finite resources; a mixture of spectrum, towers and technology often determines the amount of their network capacity.

Further, wireless network operators are under no obligation to sell their offerings at a loss. It's capitalism, after all.

But the concept of "unlimited" data services continues to create wrinkles among 4G and 5G network operators. In the early days of "unlimited" data in the 4G world, the word actually meant that users could consume a certain amount of data at full speed, and then more data at slower speeds.

In recent months, with announcements by AT&T and T-Mobile of "unlimited premium data," that's starting to change.

But the introduction of 5G technology in the US has not resulted in data parity. Data routed through a smartphone screen is still treated one way, and data routed through a smartphone's hotspot is treated another way.

As a result, today's smartphone customers are left to figure out what "unlimited" data actually means in the 5G era, and how that's different from the "unlimited" promises of other 4G, fiber and cable providers.

Related posts:

Mike Dano, Editorial Director, 5G & Mobile Strategies, Light Reading | @mikeddano